Alumni voice: Grit, determination and a mother's passion

Long after my Ph.D. defense on Dec. 6, 2010, I sat at my desk in 209 Chemistry Building

and cried — a drawn-out cry that was spontaneous and melancholic in its effect. The

lingering acidity of abject poverty in which I had grown up felt temporarily dilute

and less corrosive. Even the invisible burdens of being a first-generation student

and the first student of an assistant research professor seemed much lighter that

day. In the end, tears seemed like a befitting and therapeutic closure to an academic

journey that had ended just as implausibly as it had started.

Born to and raised by an illiterate, single mother of eight in a remote Kenyan village,

there was nothing in my unremarkable childhood that would have prepared me for a Ph.D.

Poverty was not just rampant, excruciating and humiliating, its toll on education

was explicit, exacting and vicious. Where I grew up, no one had a college degree,

much less dreams of anything bigger or better than mere existence.

In the 10 years since my defense, I am still in awe of how a bookless kid who used

a smoky kerosene lamp for 20-plus years and who had never worn shoes or brushed his

teeth until he was 15 years old, could overcome his “academic dwarfism,” get a Ph.D.

and compete with the best and brightest.

There’s no mystery to it, though. My mom, who has since passed away, is as much the

cornerstone of this success as she was its architect. In spite of — or perhaps because

of — her illiteracy, she was singularly determined to ensure that her children got

the education she missed. The pain of seeing her battered but resolute frame walking

barefoot for hours each day from distant markets to odd jobs and back again for years

just to provide the very basic food and supplies, fueled an insatiable thirst in me

that not even a Ph.D. could quench.

Looking back at those five years in graduate school and these past 10 as an industrial

scientist, my view is that, notwithstanding our advanced degrees or academic pedigree,

we are universally average with respect to innate abilities.

Time, privilege and a dose of good old luck give those with grit the tolerance they

need to stand in line the longest on their way to winning Nobel prizes and doing other

great things, even as the rest of us fade into obscurity.

Given enough time, you can teach anybody almost anything, but you can’t necessarily

teach them to be passionate about it. In the game of averages, passion — such as my

mom’s — can and often does make all the difference in our definition of success.

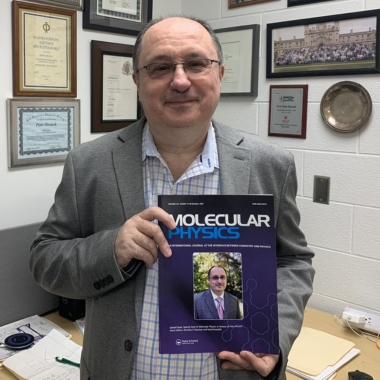

To read more from Mark Ondari (Ph.D. 2010, Prof. Kevin Walker’s group), follow him on Twitter @markondari

Source: MSUToday